US market analysts’ life just got a whole lot more complicated. As if it wasn’t difficult enough to assess what economic data means. For example, is higher unemployment actually a “good” thing? Perhaps, if you are banking on the Fed aggressively cutting rates. Or is it a “bad” thing because it suggests an economy that might be beginning to falter, and you are focused on economic growth. There simply is no correct answer, only an interpretation shaped primarily by an investor’s viewpoint at any given point in time.

Given the fluctuating machinations of market analysis, it is probably just as well that much of the economic data on which such assessments are based are built on a bedrock of boring and in most cases very boring government data. The very dullness of unemployment, inflation, and other such statistics, is actually what makes them useful in the first place. They are just statistical measures that deliver age old facts, measured in the same old way. The art of the analyst lies in how to interpret them.

These two measures of course are of fundamental political consequence and governments rise and fall on the manifestations of both cheery or bleak economic data. It is, though properly understood, that the data is just the reflection of the societal reality, and not that the other way around.

Lies, Dammed Lies, Statistics, Dammed Lies, and Lies

This may, however, no longer be the case. When at the beginning of August President Trump fired the Commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics because July’s unemployment numbers did not, in the president’s opinion, accurately reflect the booming economy.

Interestingly, US stock market investors were generally happy at the less than rosy unemployment numbers as the mild increase was interpreted, correctly, as indicating that the Federal Reserve would begin loosening monetary policy, which they did with the rate cut at their September meeting.

The potential disturbance of injecting politics directly into the institutions that produce the statistics is enormous. It doesn’t even require tampering with the data. If the impression that the data may no longer be independent and therefore could be unreliable, creeps in, then this uncertainty will alter how market participants view and treat that data.

In the context of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), this is particularly important as it is the compiler of the two most significant sources of data on which the Fed’s monetary policy is based, unemployment and inflation. The Fed’s so called dual mandate of trying to achieve maximum employment (4% or below) with target inflation (2%) revolves around BLS data. Were the idea that BLS data was politically expedient to become established, that would ultimately call into question the independence of the Fed’s monetary policy. Not in this case through direct manipulation of the Fed, but indirectly through its data. Jerome Powell frequently emphasizes how data driven the Fed’s decision-making is. So, this could mean that by jiggling the BLS numbers the administration of the day could indirectly influence the direction of monetary policy, for the good of the administration rather than for the good of the country.

Dueling with the Dual Mandate is Complicated Enough

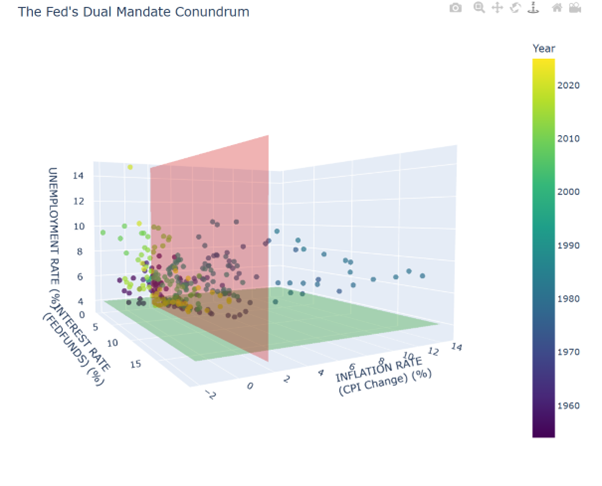

The Fed’s Dual Mandate is for the most part in practice, an aspirational goal. Look at the chart below, it illustrates the relationship between the three pillars of monetary policy—interest rates, Inflation, and unemployment—using 70 years of monthly data.

The chart can be rotated to view the three-dimensional relationship across the data.

We have included the two targets of the dual mandate as transparent floors to indicate the target inflation figure of 2% (in red) and maximum employment, which is an unemployment figure of 4% or below (in green).

What is most striking is how few data points fall within both criteria. In fact, it occurs less than 2% of the time. This stands as testimony to the difficulty of actually achieving the balance. The reality is that either inflation or unemployment, or both, are higher than its respective target most of the time.

This illustrates the complex interdependence of the economy from which the unemployment and inflation levels emanate and the tricky and thankless task the Fed has in trying to balance these two forces. Within this difficulty, one thing has been stable, the data representing each.

Imagine the useless confusion of trying to read this chart, if one felt that one couldn’t trust either the unemployment figure or the rate of inflation. Which for political reasons might be less than it would have been, if measured apolitically. Trust would be broken, creating a distorting effect on interest rates—which also would be untrustworthy, and that distrust would seep through to US Treasuries, infecting the whole US financial system.

This is the potential risk of politicized data. Investors cannot ignore this risk and must now monitor future BLS data for anything that suggests that it is exhibiting any political tampering. ■

© 2025 Plotinus Asset Management. All rights reserved.

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of any material on this site without written permission is prohibited.

Image Credit: Sychugina at Shutterstock.